BY GUY LEVI

If you don’t think we are in an educational paradigm shift, specifically to a skills-based curriculum, don’t read this piece. If you hesitate, try it out, you can leave anytime. Suppose you do think we are moving toward a new world of learning, wishing to prepare our children / students / future citizens / future leaders to be able to face the challenges the 21st century creates. In that case, you may find, here, helpful and sometimes innovative information. You don’t have to fly to Chisinau next week, but next year, when the Moldova case transforms theory and practice into one entity, you may consider coming to Tekwill.

Moldova is not a rich country, to say the least, by EU or OECD standards or criteria; however, it is rich in young human capital, but I don’t think the Moldovans are aware of it. My experience in a Design 2 Sprint, in the last week of August 2022, with nearly 60 educators and, for times, 30 students at the great space of Tekwill, proved it (at least for me). Now they should be aware of it. Let me start with a list of attributes one needs to be a potential innovator in learning. Yes, we focused on learning skills or skills-based learning during the design sprint. So the list starts with the ability to listen. Next is the capacity to be part of an empathetic dialogue, a genuinely scarce resource, empathy. Third comes the capability of teamwork. Next is the ability to move faster and be agile. Last is the hidden value that characterized each of the participants. They all had something that made them unique, and they had to expose it, take it out, and use it for their team’s success, in our case, pedagogical success. There are more relevant attributes; however, these are the most important for the success of the process – the design sprint.

Reflecting on this week, I realized that human capital is the most critical condition for pedagogical success, and the above five attributes are all human capital characteristics. I was lucky to have these rooted in the Moldovan teams. Yet, this design sprint week could not exist without the leadership of Tatiana Alexeev, the director of “Tekwill in Every School”, the EdTech program of Moldova’s education system. Tatiana is an innovator and risk taker, enthusiastic about bringing her country’s education to new heights, aiming to make the Z generation future “stay” in Moldova for the country’s future.

Now, let’s elaborate and detail this design sprint week in Tekwill. As already mentioned, it was part of “Tekwill in Every School”, a project aiming to lay the groundwork for education transformation in Moldova. We gathered dozens of educators to initiate the paradigm shift from a content-based curriculum to a skills-based curriculum.

The design sprint’s goals were to develop pedagogical digital transformation in Moldova’s education system, utilizing the OECD Education and Skills 2030 Learning Compass ecosystem to enhance the shift to a skills-based curriculum. We employed design thinking and lean startup methodologies, specifically the Minimum Viable Product (MVP) method. But first, let’s talk a bit about the design sprint process, which is, as we all know, a proven methodology for solving problems through designing, prototyping, and testing ideas with users. When adopting design sprint to education, we bring agility to its peak. Think of an educational learning module developed in one and a half days, tested with students, then analyzed pedagogically, and then ready to go to school to practice. The educators in the design sprint looked at me as if I were an extraterrestrial; however, after one day and a half, I was looking at them thinking they were the extraterrestrials, running the MVP enthusiastically with students as if it was the climax of their career. In practical terms, the target of the design sprint was to acquire the participants with the knowledge and skills to become mentors of pedagogical innovation, equipped with the methods needed to lead the schools’ teams and the entire school gradually to a skills-based learning culture.

We cannot escape the story of the five days of design sprint day-by-day, as it is imperative to grasp the real essence of it. To provide the big picture, we had two 3-hour sessions online before I arrived 4 in Chisinau. In these two sessions, we learned about the design sprint program and the methods and practiced some of the canvases using collaborative digital tools. Hence, we did not start the design sprint from scratch. The first two days were dedicated to developing an MVP of a skills-based module and testing it with local students; the third and fourth days were aimed at analyzing the modules and sharing the results in a pitching session. The last day was devoted to mapping the schools’ ecosystem using methods of systems innovation to prepare for the first implementation stage. From this point, we will use the digital storytelling method using many photographs and less text. Last note before we start with day 1: It is imperative to plan the design sprint process accurately and in detail. At the same time, it is crucial to be agile and change the plan according to the real-time flow, to the actual actions of the participants, to their authentic and genuine achievements, sometimes unexpected achievements which are serendipity-like.

Day 1

On the first day, the groups began planning a skills-based module using the Learning Compass ecosystem with an additional criterion, I added, of Digital Pedagogy, utilizing Miro – a collaborative and interactive digital whiteboard and a physical canvas to complement the digital environment. The physical canvas promotes discourse, discussion, and reciprocity, but maybe the most important function of this canvas was the ability to view the whole system together. For some, it was a revelation. Regarding digital pedagogy, I received some criticism using these two words together, explaining that there is no such pedagogy that is digital. It was anticipated, so here is my definition of digital pedagogy: the use of digital tools to promote or improve learning. Ten words, that’s it, so if the digital tool does not improve learning, don’t use it.

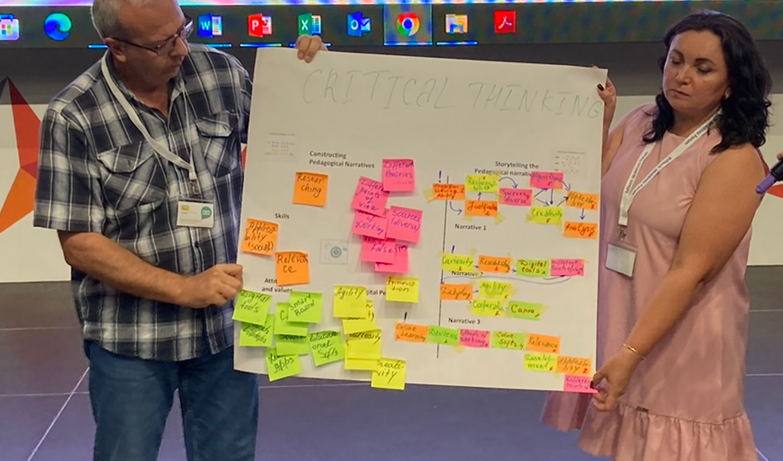

The following photographs illustrate the groups’ physical work on a canvas and virtual work on Miro. After every group activity, we paused to share the learning process using the “rotation” method. All participants gathered around the groups’ tables (as seen in the photos). This part is essential as it provides everyone time to reflect, learn, think about their work and improve it.

The second part of the first day was to develop three different narratives for a skills-based module, again using physical canvas and virtual illustration on Miro. This activity needs some elaboration, as most participants were engaged in their ideas on the skills-based module and were eager to move forward with the development. No, they must “slow down” a bit and begin to organize the mapping according to the agreed criteria of the skills they chose – be it critical thinking, creativity, media literacy, teamwork, digital literacy, or learning to learn (the actual choices of the groups). After the arrangement of criteria, they were asked to develop, as mentioned above, three different narratives in a storytelling language. Three, not one, not two. They must have alternatives and critically compare their ideas to be more precise and accurate in developing the skills-based module.

I thought it was quite a productive and fruitful first day.

Day 2

The second day focused on building and testing the Minimum Viable Product (MVP), the heart of the Lean Startup methodology, which was connected to the Leaning Compass by refining the learners’ knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values they will acquire during the learning of the module. The essential pedagogical part of working on the MVP was the necessity to break the narrative selected to its atomic components. Then, reassemble them in a new way that will best connect the knowledge, values, and sub-skills, with the help of digital tools, to a semi-holistic new and more innovative learning module. How do we know that it was more creative and innovative? Well, we don’t need to know; they, the participants, the creators of the skills-based module, know. How do they know it? After an iterative process of refining the pedagogy of the MVP, they surely know.

The second part of the day was dedicated to testing the MVP with Moldovan high school students who came to be co-designers of the Skills-based modules.

Examples of the modules developed by the groups:

- Development of communication skills, teamwork, and creativity by the collaborative design of a new learning space for the school.

- Using a Podcast as a pedagogical tool to promote media literacy, collaboration, reflective skills, listening skills, and empathy.

- Blog creation to promote critical thinking, teamwork, and media literacy.

- Virtual learning partnership to increase social responsibility in dealing with used batteries and electronics recycling and promote critical thinking and decision-making skills (in the ecosystem of the Learning Compass, it is in the domain of Transformative Competencies).

The students actively learned while the teachers guided them and digitally documented the learning process. At the end of the learning cycle, the teachers conducted ethnographic interviews with the students about their learning experiences. They received a load of comments and insights about their skills-based modules.

The end of the day was marked by the students providing feedback on their learning in a plenary session. The importance of this “public” feedback was twofold: first, to promote sharing knowledge and transparency; and second, to emphasize student agency, co-agency, and co-design.

Day 3

The third day was dedicated to analyzing the MVP, improving the skills-based learning modules, and digitally producing a “pitch” of the module for a Demo-day-like event. For the analysis, we used a work-in-progress model development called UPIX. The combination of User Interface (UI) and User eXperience (UX) and adding User Pedagogy (UP) created UPIX. This model is being developed with an Israeli Teacher Center executive team, Miri Even-Chen (director), Gitit Peleg (deputy director), Maya Cohen (senior learning designer), and Racheli Peleg (senior learning designer). They have full credit for UPIX. We have been working on this multi-dimensional model since the beginning of 2022, and we found it feasible and practical for planning, developing, implementing, and evaluating learning processes. We think that today development and implementation go together, so we are testing UPIX in diverse settings, one of them in Moldova, here as an evaluation model.

UPIX required the groups to rigorously and critically look at the pedagogy, the experience of the learners, the learning environment, digital tools, etc., of their MVP. The separation of these three concepts or principles – UP-UX-UI, enabled the Moldovan educators to analyze the MVP in a novel way, look at the granular components in each concept and make connections between and among them, refining the skills-based learning module, and improving their understanding. Again, the groups shared their analysis for mutual learning. Furthermore, we found sharing a proper iterative method. Keep sharing, it is beneficial and valuable for self and group reflection (when preparing the presentation) and for mutual learning (getting new ideas from other groups).

The groups then started to work on the “pitches” planned for day 4. The work on the pitch required them to use their meta-cognitive skills, thinking about their module structure, its connection to the 12 Learning Compass, and for the first time in the design sprint, how they will implement it in their school. Important note: it was critical to free them from thinking about practical implementation during the development process, so their creativity and innovative thinking could flourish. Now, when they experience the entire cycle of the MVP, we introduce the practical implementation issue.

Day 4

On the fourth day, we virtually hosted Mrs. Suzanne Dillon, chair of the Advisory Group of the OECD Global Forum on the Future of Education and Skills 2030, who talked about the project and connected it to the work of the groups.

Suzanne talked about the Learning Compass and elaborated that “the metaphor of a compass was chosen because it captures and holds in tension a number of important ideas – that learning is a journey taken through life; that diversity means that we can only point the direction rather than prescribe the specific route; that uncertainty and unpredictability are navigable and so on. The end goal is wellbeing.” These words summarized the work of the groups during the first three days and were well documented in their pitches. At the end of the seven pitches, Suzanne commented by stressing that the “project is currently focused on developing a Teaching Compass, to complement the Learning Compass. We are learning that, at work, research evidence suggests that people have three core needs: autonomy, belonging and contribution. Enacting teacher policies which address these is more likely to encourage commitment, energy and creativity, all attributes which enhance 13 the learning experiences of teachers and students and which support wellbeing, the ultimate goal identified in our Learning Compass.” It is crucial, in the case of the shift to a skills-based curriculum to make these important connections and having Suzanne Dillon with us at this point of the design sprint, served as a “certification” to the work of the educators, and somewhat a proof of the direction they have taken.

Day 5

The last day of the design sprint was dedicated to Systems Innovation. The groups mapped the schools’ ecosystems to observe the broader context of the shift to a skills-based curriculum. The criteria to map the school ecosystem were: curriculum, learning space, teachers, professional development, organizational structure, stakeholders and partners, and innovation. The groups were asked to categorize their work according to strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities and to focus on the opportunities they saw in the shift to a skills-based curriculum. That was just the beginning.

Takeaways of the Design Sprint in Moldova

The method proved to be very successful when you want to promote significant transformation, in an agile environment, in education. We must free the participants from their daily reality and provide them with the space and atmosphere to create, collaborate, make mistakes, test their innovative ideas, learn new methods, take risks, be happy and have fun. What did they take from this week?

- They learned and experienced Skills-based curriculum development

- They became acquainted with Design Thinking and Lean Startup, and MVP methods of learning modules development

- They decomposed theories, concepts, and models, broke them into their components, and reassembled them into new and innovative structures (developed creativity and deeper understanding)

- They understood that the integration of digital pedagogy is a “game changer” in the shift to a skills-based curriculum

- They grasped that collective agency and collective intelligence are essential for the future of learning and the future of education

- They recognized the significance of learner-centered development and the MVP process for the design of future curriculum

- They experienced the importance of “failure for learning” in the development process

- They internalized the significance of sharing and modeling in a pedagogical development

- They understood the importance of agility in today’s professional work

The next phase in the shift to a skills-based curriculum in Moldova is to develop a qualitative approach to skills evaluation and assessment. We will follow the design sprint method, making collective intelligence and collective agency the keys to our process. We will gather principals, teachers, and students in Tekwill to plan, design, implement and experience skills-based learning for assessment.

This material was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its content represents the sole responsibility of the “EU4Moldova: Startup City Cahul” project, financed by the European Union. The content of the material belongs to the authors and does not necessarily reflect the vision of the European Union.